Key Takeaways

- Measurement of any initiative is driven by the goals for that initiative, and it is important to ensure these goals are aligned across stakeholders.

- Sometimes you can do more measurement yourself than you think you can, and other times research partners can add more value than you realize.

- Goals and routines can and should change over time, and it is important to continuously revisit them.

Context

No matter the scope, motivation, or stage of your measurement project, there are a few critical decisions that will determine its success. These decisions can often be made implicitly, with little team-wide time or reflection spent on them. Because these decisions can make or break a project, they often remain hidden reasons for project derailment. However, when these decisions are made explicitly, collectively, and transparently, measurement is more likely to provide useful information and unearth actionable insights – and even when it doesn’t, it is far easier to determine why.

As you embark upon measuring to improve and inform teaching and learning, you may find the following questions helpful. Even if you’re already measuring, it’s not too late to reflect or even explicitly reconsider these questions to ensure project success.

- What are the underlying goals of the initiative you are measuring? What is the instructional problem or system challenge you are aiming to solve with this initiative? Does everyone agree with it?

- What are the data, analysis, design, and other measurement resources that you have? Can any of these adequately support your measurement goals? Are there resource gaps that can or should be filled through research partnerships?

- How will your measurement activities support your goals? Are there specific contexts or pain points that require unique measurement processes (like embedded data collection) or routines (e.g., external reporting requirements)? Have there been routines that have not worked well for you in the past?

Read on for guidance on answering these questions.

Where to begin?

Even within a single organization or project, understanding goals – and ensuring a shared understanding of goals – is a complex task. In school systems, this task is further complicated by differences in language and practices that may be common in one department or team but not another. However, agreeing on a shared set of goals is key to the success of any measurement process.

Logic modeling, a systematic and visual way to outline your understanding of the relationships among the resources you have to operate your project, the activities you plan, and the changes or results you hope to achieve, is one way to overcome these challenges. The process for developing a logic model allows for explicit sharing of different perspectives and reaching consensus on the goals of a project and partnership. Once created, the model is a clear resource for documenting shared understanding and plans. There are many ways to develop a logic model, but the process is more important than the actual format used. The key here is to ensure that all stakeholders are included in this process to facilitate buy-in and participation in the measurement project. One great resource for learning about and building logic models is the Education Logic Model app produced by the Institute of Education Sciences’ Pacific Regional Education Lab.

Another important step in clarifying the goals of the measurement project at the beginning is to explicitly and collaboratively identify the questions to be answered. For example, TLA partnered with two school systems to measure their personalized learning initiatives. Both school systems wanted to know what practices within the initiative to scale and how to scale them. However, for each partner, the specific questions that we answered were very different, even though the overall goal was essentially the same.

For Distinctive Schools, our specific question was how to ensure the teaching practices being built and measured continued to align with the system’s overall goals for personalized learning even as those practices were evolving within professional development, scaling across new schools, and being sustained by educators over multiple years, with new students.

For Leadership Public Schools (LPS), the questions we answered included, “What are good metrics or indicators of “success” based on LPS’ implementation goals and documented practices described above?”, and “Is Navigate Math successful in meeting its goals as measured by the metrics/indicators described above, compared to a group of matched students?”

In both cases, because we had spent time outlining the specific questions to be answered based on the shared goals we set for the measurement project, we were able to use data that the school systems already had or were already collecting to make practical, actionable, and data-driven recommendations to scale and sustain their initiatives.

How to manage the work?

There are multiple areas of measurement in which you may already have the tools and systems to do it yourself. For example, your system may already have a research and evaluation office, staff member, or tool that can help you conduct measurement activities at no additional cost (some existing tools are discussed below). Additionally, there may be (and often are!) data systems that you already have (or have access to) that can be used when measuring. Three areas that may require partnership are data infrastructure, analysis, and designing and interpreting your measurement process.

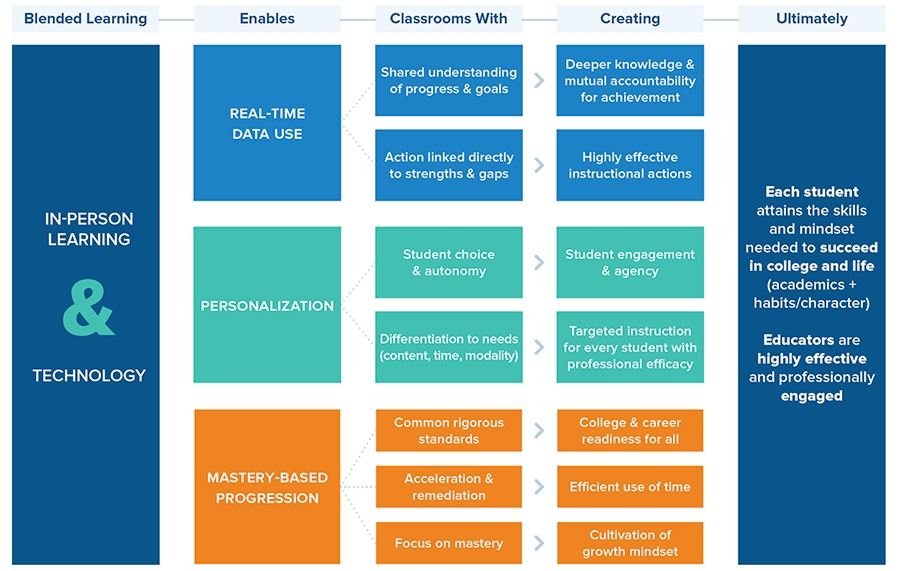

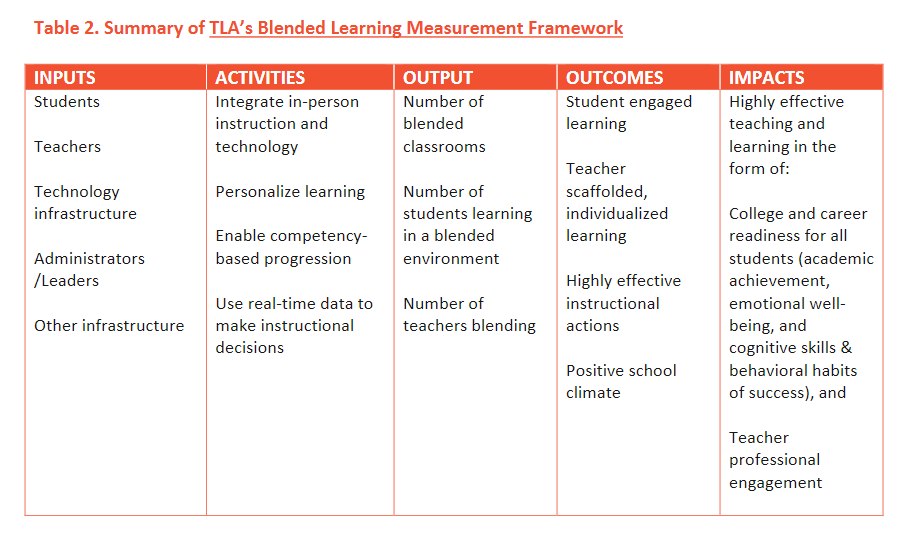

When deciding whether to partner in order to meet data infrastructure needs, be sure to consider all the data you’re already collecting, storing, and managing – even if those were designed for a different purpose. You can use your logic model to identify these existing data. An example of a simplified logic model or framework for measuring blended learning is shown below. Details about the data that are relevant to this framework are included in our Blended Learning Measurement Framework.

As discussed more deeply in our District Guide to Blended Learning Measurement, some data you may already have available for measurement include:

- Mean or “norm” scores from standardized tests

- Percentile-equivalent scores from standardized tests

- Expected or predicted growth scores from benchmark tests

- Proficiency ranks or proficiency rates from annual state tests

- Other scores from district- or state-wide tests and measures

When it comes to analysis, if you don’t have the in-house capacity but do have folks who are data savvy (e.g., your school’s assessment team leader), you may find free tools like the Rapid-Cycle Evaluation Coach or EdTech Pilot Framework are all you need. However, if you do not have the in-house capacity, research partners may prove invaluable in either of the above situations or when grappling with measurement design and interpretation questions. Researchers may be able to answer more technical questions quickly without much effort. If you do decide to partner with a researcher, be sure to read about some key considerations for that partnership, including the potential costs of such partnership, in the links below.

Ongoing routines

Completing the activities within a measurement project can sometimes eclipse reflecting on how things are going. Some projects can lose steam and “fizzle,” or others go on and on with no end in sight. It’s important to revisit goals regularly and consider how well routines are working to prevent this from happening. For short-term projects that can be completed within a school year or even a semester, be sure to clearly identify early in the project an “endpoint” or final milestone that all stakeholders agree on. For longer-term, multi-year projects, build in meetings or other communication points to review past activities and identify upcoming and future goals. After a measurement project (or stage) ends, conduct a post-project review and document lessons learned so that the next project can benefit. If your system does not already have processes for reviewing goals or activities and documenting lessons learned, you may find these examples helpful to adapt or build your own.

Take it further

You may find, after outlining the measurement project that you can accomplish with existing resources, that there is actually a deeper project that you need to conduct to answer the questions that will help you improve your initiative. If this is the case, you’ll need to reflect on how to access and deploy additional resources. One example of how a district approached this problem is outlined in our Blended Learning Snapshot: Data-Driven Ed Tech Decisions. Additional guidance about reflecting and making decisions about measurement can also be found in our Leadership Design Choices Problem of Practice series.